Open-source software (OSS) is computer software that is released under a license in which the copyright holder grants users the rights to use, study, change, and distribute the software and its source code to anyone and for any purpose.[1][2] Open-source software may be developed in a collaborative, public manner. Open-source software is a prominent example of open collaboration, meaning any capable user is able to participate online in development, making the number of possible contributors indefinite. The ability to examine the code facilitates public trust in the software.[3]

Open-source software development can bring in diverse perspectives beyond those of a single company. A 2008 report by the Standish Group stated that adoption of open-source software models has resulted in savings of about $60 billion per year for consumers.[4][5]

Open-source code can be used for studying and allows capable end users to adapt software to their personal needs in a similar way user scripts and custom style sheets allow for web sites, and eventually publish the modification as a fork for users with similar preferences, and directly submit possible improvements as pull requests.

Definitions edit

The Open Source Initiative's (OSI) definition is recognized by several governments internationally[6] as the standard or de facto definition. OSI uses The Open Source Definition to determine whether it considers a software license open source. The definition was based on the Debian Free Software Guidelines, written and adapted primarily by Perens.[7][8][9] Perens did not base his writing on the "four freedoms" from the Free Software Foundation (FSF), which were only widely available later.[10]

Under Perens' definition, open source is a broad software license that makes source code available to the general public with relaxed or non-existent restrictions on the use and modification of the code. It is an explicit "feature" of open source that it puts very few restrictions on the use or distribution by any organization or user, in order to enable the rapid evolution of the software.[11]

According to Feller et al. (2005), the terms "free software" and "open source software" should be applied to any "software products distributed under terms that allow users" to use, modify, and redistribute the software "in any manner they see fit, without requiring that they pay the author(s) of the software a royalty or fee for engaging in the listed activities."[12]

Despite initially accepting it,[13] Richard Stallman of the FSF now flatly opposes the term "Open Source" being applied to what they refer to as "free software". Although he agrees that the two terms describe "almost the same category of software", Stallman considers equating the terms incorrect and misleading.[14] Stallman also opposes the professed pragmatism of the Open Source Initiative, as he fears that the free software ideals of freedom and community are threatened by compromising on the FSF's idealistic standards for software freedom.[15] The FSF considers free software to be a subset of open-source software, and Richard Stallman explained that DRM software, for example, can be developed as open source, despite that it does not give its users freedom (it restricts them), and thus does not qualify as free software.[16]

Open-source software licensing edit

When an author contributes code to an open-source project (e.g., Apache.org) they do so under an explicit license (e.g., the Apache Contributor License Agreement) or an implicit license (e.g. the open-source license under which the project is already licensing code). Some open-source projects do not take contributed code under a license, but actually require joint assignment of the author's copyright in order to accept code contributions into the project.[17]

Examples of free software license / open-source licenses include Apache License, BSD license, GNU General Public License, GNU Lesser General Public License, MIT License, Eclipse Public License and Mozilla Public License.

The proliferation of open-source licenses is a negative aspect of the open-source movement because it is often difficult to understand the legal implications of the differences between licenses. With more than 180,000 open-source projects available and more than 1400 unique licenses, the complexity of deciding how to manage open-source use within "closed-source" commercial enterprises has dramatically increased. Some are home-grown, while others are modeled after mainstream FOSS licenses such as Berkeley Software Distribution ("BSD"), Apache, MIT-style (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), or GNU General Public License ("GPL"). In view of this, open-source practitioners are starting to use classification schemes in which FOSS licenses are grouped (typically based on the existence and obligations imposed by the copyleft provision; the strength of the copyleft provision).[18]

An important legal milestone for the open source / free software movement was passed in 2008, when the US federal appeals court ruled that free software licenses definitely do set legally binding conditions on the use of copyrighted work, and they are therefore enforceable under existing copyright law. As a result, if end-users violate the licensing conditions, their license disappears, meaning they are infringing copyright.[19] Despite this licensing risk, most commercial software vendors are using open-source software in commercial products while fulfilling the license terms, e.g. leveraging the Apache license.[20]

Open-source software development edit

Development model edit

In his 1997 essay The Cathedral and the Bazaar, open-source influential contributor Eric S. Raymond suggests a model for developing OSS known as the bazaar model.[21] Raymond likens the development of software by traditional methodologies to building a cathedral, with careful isolated work by individuals or small groups.[21] He suggests that all software should be developed using the bazaar style, with differing agendas and approaches.[21]

In the traditional model of development, which he called the cathedral model, development takes place in a centralized way.[21] Roles are clearly defined.[21] Roles include people dedicated to designing (the architects), people responsible for managing the project, and people responsible for implementation.[21] Traditional software engineering follows the cathedral model.[21]

The bazaar model, however, is different.[21] In this model, roles are not clearly defined.[21] Some proposed characteristics of software developed using the bazaar model should exhibit the following patterns:[22]

Users should be treated as co-developers: The users are treated like co-developers and so they should have access to the source code of the software.[22] Furthermore, users are encouraged to submit additions to the software, code fixes for the software, bug reports, documentation, etc. Having more co-developers increases the rate at which the software evolves.[22] Linus's law states that given enough eyeballs all bugs are shallow.[22] This means that if many users view the source code, they will eventually find all bugs and suggest how to fix them.[22] Some users have advanced programming skills, and furthermore, each user's machine provides an additional testing environment.[22] This new testing environment offers the ability to find and fix a new bug.[22]

Early releases: The first version of the software should be released as early as possible so as to increase one's chances of finding co-developers early.[22]

Frequent integration: Code changes should be integrated (merged into a shared code base) as often as possible so as to avoid the overhead of fixing a large number of bugs at the end of the project life cycle.[22][23] Some open-source projects have nightly builds where integration is done automatically.[22]

Several versions: There should be at least two versions of the software.[22] There should be a buggier version with more features and a more stable version with fewer features.[22] The buggy version (also called the development version) is for users who want the immediate use of the latest features and are willing to accept the risk of using code that is not yet thoroughly tested.[22] The users can then act as co-developers, reporting bugs and providing bug fixes.[22][23]

High modularization: The general structure of the software should be modular allowing for parallel development on independent components.[22]

Dynamic decision-making structure: There is a need for a decision-making structure, whether formal or informal, that makes strategic decisions depending on changing user requirements and other factors.[22] Compare with extreme programming.[22]

The process of Open source development begins with a requirements elicitation where developers consider if they should add new features or if a bug needs to be fixed in their project.[23] This is established by communicating with the OSS community through avenues such as bug reporting and tracking or mailing lists and project pages.[23] Next, OSS developers select or are assigned to a task and identify a solution. Because there are often many different possible routes for solutions in OSS, the best solution must be chosen with careful consideration and sometimes even peer feedback.[23] The developer then begins to develop and commit the code.[23] The code is then tested and reviewed by peers.[23] Developers can edit and evolve their code through feedback from continuous integration.[23] Once the leadership and community are satisfied with the whole project, it can be partially released and user instruction can be documented.[23] If the project is ready to be released, it is frozen, with only serious bug fixes or security repairs occurring.[23] Finally, the project is fully released and only changed through minor bug fixes.[23]

Advantages edit

Open-source software is usually easier to obtain than proprietary software, often resulting in increased use. Additionally, the availability of an open-source implementation of a standard can increase adoption of that standard.[24] It has also helped to build developer loyalty as developers feel empowered and have a sense of ownership of the end product.[25]

Moreover, lower costs of marketing and logistical services are needed for OSS. It is a good tool to promote a company's image, including its commercial products.[26] The OSS development approach has helped produce reliable, high quality software quickly and inexpensively.[27]

Open-source development offers the potential to quicken innovation and the creation of innovation and social value. In France for instance, a policy that incentivized government to favor free open-source software increased to nearly 600,000 OSS contributions per year, generating social value by increasing the quantity and quality of open-source software. This policy also led to an estimated increase of up to 18% of tech startups and a 14% increase in the number of people employed in the IT sector.[28]

It is said to be more reliable since it typically has thousands of independent programmers testing and fixing bugs of the software. Open source is not dependent on the company or author that originally created it. Even if the company fails, the code continues to exist and be developed by its users. Also, it uses open standards accessible to everyone; thus, it does not have the problem of incompatible formats that may exist in proprietary software.

It is flexible because modular systems allow programmers to build custom interfaces, or add new abilities to it and it is innovative since open-source programs are the product of collaboration among a large number of different programmers. The mix of divergent perspectives, corporate objectives, and personal goals speeds up innovation.[29]

Moreover, free software can be developed in accordance with purely technical requirements. It does not require thinking about commercial pressure that often degrades the quality of the software. Commercial pressures make traditional software developers pay more attention to customers' requirements than to security requirements, since such features are somewhat invisible to the customer.[30]

Development tools edit

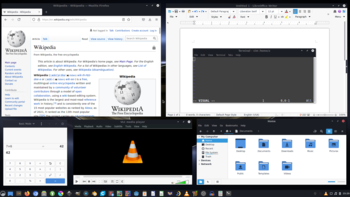

In OSS development, tools are used to support the development of the product and the development process itself.[31]

Revision control systems such as Concurrent Versions System (CVS) and later Subversion (SVN) and Git are examples of tools, often themselves open source, help manage the source code files and the changes to those files for a software project.[32] The projects are frequently stored in "repositories" that are hosted and published on source-code-hosting facilities such as Launchpad, GitHub, GitLab, and SourceForge.[33]

Open-source projects are often loosely organized with "little formalised process modelling or support", but utilities such as issue trackers are often used to organize open-source software development.[31] Commonly used bugtrackers include Bugzilla and Redmine.[34]

Tools such as mailing lists and IRC provide means of coordination among developers.[31] Centralized code hosting sites also have social features that allow developers to communicate.[33]

Organizations edit

Some of the "more prominent organizations" involved in OSS development include the Apache Software Foundation, creators of the Apache web server; the Linux Foundation, a nonprofit which as of 2012[update] employed Linus Torvalds, the creator of the Linux operating system kernel; the Eclipse Foundation, home of the Eclipse software development platform; the Debian Project, creators of the influential Debian GNU/Linux distribution; the Mozilla Foundation, home of the Firefox web browser; and OW2, European-born community developing open-source middleware. New organizations tend to have a more sophisticated governance model and their membership is often formed by legal entity members.[35]

Open Source Software Institute is a membership-based, non-profit (501 (c)(6)) organization established in 2001 that promotes the development and implementation of open source software solutions within US Federal, state and local government agencies. OSSI's efforts have focused on promoting adoption of open-source software programs and policies within Federal Government and Defense and Homeland Security communities.[36]

Open Source for America is a group created to raise awareness in the United States Federal Government about the benefits of open-source software. Their stated goals are to encourage the government's use of open source software, participation in open-source software projects, and incorporation of open-source community dynamics to increase government transparency.[37]

Mil-OSS is a group dedicated to the advancement of OSS use and creation in the military.[38]

Funding edit

Companies whose business centers on the development of open-source software employ a variety of business models to solve the challenge of how to make money providing software that is by definition licensed free of charge. Each of these business strategies rests on the premise that users of open-source technologies are willing to purchase additional software features under proprietary licenses, or purchase other services or elements of value that complement the open-source software that is core to the business. This additional value can be, but not limited to, enterprise-grade features and up-time guarantees (often via a service-level agreement) to satisfy business or compliance requirements, performance and efficiency gains by features not yet available in the open source version, legal protection (e.g., indemnification from copyright or patent infringement), or professional support/training/consulting that are typical of proprietary software applications.

Sociological and demographic questions edit

Motivations edit

A question of frequent interest among researchers is what motivates writers of open-source software, a behavior that may be "seemingly irrational."[39] While some sociologists theorized that external motivations—such as "better jobs" and "career advancement"—were the primary drivers for open-source software developers, Lakhani and Wolf found that "enjoyment-based intrinsic motivation"—"how creative a person feels when working on the project" was the most important driver.[40]

Demographics edit

In a 2005 study, Ghosh posited that the vast majority of open-source software developers identified as male, finding it "unlikely" that the proportion of female developers in the committee was "much higher than 5-7 percent."[41] Additionally, Ghosh found that more than 60% of developers were between the ages of 16 and 25.

Open Software Movement edit

History edit

Further information: History of free and open-source software

In the early days of computing, such as the 1950s and into the 1960s, programmers and developers shared software to learn from each other and evolve the field of computing.[42] For example, Unix included the operating system source code for users.[42] Eventually, the commercialization of software in the years 1970–1980 began to prevent this practice.[42] However, academics still often developed software collaboratively.[42]

In response, the open source movement was born out of the work of skilled programmer enthusiasts, widely referred to as hackers or hacker culture.[43] One of these enthusiasts, Richard Stallman, was a driving force behind the free software movement, which would later allow for the open source movement.[43] In 1984, he resigned from MIT to create a free operating system, GNU, after the programmer culture in his lab was stifled by proprietary software preventing source code from being shared and improved upon.[43] GNU was UNIX compatible, meaning that the programmer enthusiasts would still be familiar with how it worked.[43] However, it quickly became apparent that there was some confusion with the label Stallman had chosen of free software, which he described as free as in free speech, not free beer, referring to the meaning of free as freedom rather than price.[43] He later expanded this concept of freedom to the four essential freedoms.[43] Through GNU, open source norms of incorporating others' source code, community bug fixes and suggestions of code for new features appeared.[43] In 1985, Stallman founded the Free Software Foundation (FSF) to promote changes in software and to help write GNU.[43] In order to prevent his work from being used in proprietary software, Stallman created the concept of copyleft, which allowed the use of his work by anyone, but under specific terms.[43] To do this, he created the GNU General Public License (GNU GPL) in 1989, which was updated in 1991.[43] In 1991, GNU was combined with the Linux kernel written by Linus Torvalds, as a kernel was missing in GNU.[44] The operating system is now usually referred to as Linux.[43] Throughout this whole period, there were many other free software projects and licenses around at the time, all with different ideas of what the concept of free software was and should be, as well as the morality of proprietary software, such as Berkely Software Distribution, TeX, and the X Windows System.[45]

As free software developed, the Free Software Foundation began to look how to bring free software ideas and perceived benefits to the commercial software industry.[45] It was concluded that FSF's social activism was not appealing to companies and they needed a way to rebrand the free software movement to emphasize the business potential of sharing and collaborating on software source code.[45] The term open source was suggested by Christine Peterson in 1998 at a meeting of supporters of free software.[43] Many in the group felt the name free software was confusing to newcomers and holding back industry interest and they readily accepted the new designation of open source, creating the Open Source Initiative (OSI) and the OSI definition of what open source software is.[43] The Open Source Initiative's (OSI) definition is now recognized by several governments internationally as the standard or de facto definition.[44] The definition was based on the Debian Free Software Guidelines, written and adapted primarily by Bruce Perens.[46] The OSI definition differed from the free software definition in that it allows the inclusion of proprietary software and allows more liberties in its licensing.[43] Some, such as Stallman, agree more with the original concept of free software as a result because it takes a strong moral stance against proprietary software, through there is much overlap between the two movements in terms of the operation of the software.[43]

While the Open Source Initiative sought to encourage the use of the new term and evangelize the principles it adhered to, commercial software vendors found themselves increasingly threatened by the concept of freely distributed software and universal access to an application's source code, with an executive of Microsoft calling open source an intellectual property destroyer in 2001.[47] However, while free and open-source software (FOSS) has historically played a role outside of mainstream private software development, companies as large as Microsoft have begun to develop official open source presences on the Internet.[47] IBM, Oracle, and State Farm are just a few of the companies with a serious public stake in today's competitive open source market, marking a significant shift in the corporate philosophy concerning the development of FOSS.[47]

Future edit

The future of the open source software community, and the free software community by extension, has become successful if not confused about what it stands for.[48] For example, Android and Ubuntu are examples milestones of success in the open source software rise to prominence from the sidelines of technological innovation as it existed in the early 2000s.[48] However, some in the community consider them failures in their representation of OSS due to issues such as the downplaying of the OSS center of Android by Google and its partners, the use of an Apache license that allowed forking and resulted in a loss of opportunities for collaboration within Android, the prioritization of convivence over freedom in Ubuntu, and features within Ubuntu that track users for marketing purposes.[48]

The use of OSS has become more common in business with 78% of companies reporting that they run all or part of their operations on FOSS.[48] The popularity of OSS has risen to the point that Microsoft, a once detractor of OSS, has included its use in their systems.[48] However, this success has raised concerns that will determine the future of OSS as the community must answer questions such as what OSS is, what should it be, and what should be done to protect it, if it even needs protecting.[48] All in all, while the free and open source revolution has slowed to a perceived equilibrium in the market place, that does not mean it is over as many theoretical discussions must take place to determine its future.[48]

Comparisons with other software licensing/development models edit

Closed source / proprietary software edit

Main article: Comparison of open-source and closed-source software

Open source software differs from proprietary software in that it is publicly available, the license requires no fees, modifications and distributions are allowed under license specifications.[49] All of this works to prevent a monopoly on any OSS product, which is a goal of proprietary software.[49] Proprietary software limits their customers' choices to either committing to using that software, upgrading it or switching to other software, forcing customers to have their software preferences impacted by their monetary cost.[49] The ideal case scenario for the proprietary software vendor would be a lock-in, where the customer does not or cannot switch software due to these costs and continues to buy products from that vendor.[49]

Within proprietary software, bug fixes can only be provided by the vendor, moving platforms requires another purchase and the existence of the product relies on the vendor, who can discontinue it at any point.[43] Additionally, proprietary software does not provide its source code and cannot be altered by users.[43] For businesses, this can pose a security risk and source of frustration, as they cannot specialize the product to their needs, and there may be hidden threats or information leaks within the software that they cannot access or change.[43]

Free Software edit

Main article: Alternative terms for free software

See also: Comparison of free and open-source software licenses

Under OSI's definition, open source is a broad software license that makes source code available to the general public with relaxed or non-existent restrictions on the use and modification of the code.[50] It is an explicit feature of open source that it puts very few restrictions on the use or distribution by any organization or user, in order to enable the rapid evolution of the software.[50]

Richard Stallman, leader of the Free software movement and member of the free software foundation opposes the term open source being applied to what they refer to as free software.[51] Although he agrees that the two terms describe almost the same category of software, Stallman considers equating the terms incorrect and misleading.[51] He believes that the main difference is that by choosing one term over the other lets others know about what one's goals are: development (open source) or a social stance (free software).[52] Nevertheless, there is significant overlap between open source software and free software.[51] Stallman also opposes the professed pragmatism of the Open Source Initiative, as he fears that the free software ideals of freedom and community are threatened by compromising on the FSF's idealistic standards for software freedom.[52] The FSF considers free software to be a subset of open-source software, and Richard Stallman explained that DRM software, for example, can be developed as open source, despite how it restricts its users, and thus does not qualify as free software.[51]

The FSF said that the term open source fosters an ambiguity of a different kind such that it confuses the mere availability of the source with the freedom to use, modify, and redistribute it.[51] On the other hand, the term free software was criticized for the ambiguity of the word free, which was seen as discouraging for business adoption, and for the historical ambiguous usage of the term.[52]

Developers have used the alternative terms Free and Open Source Software (FOSS), or Free/Libre and Open Source Software (FLOSS), consequently, to describe open-source software that is also free software.[53]

Source-available software edit

Main article: Source-available software

Software can be distributed with source code, which is a code that is readable.[54] Software is source available when this source code is available to be seen.[54] However to be source available or FOSS, the source code does not need to be accessible to all, just the users of that software.[54] While all FOSS software is source available because this is a requirement made by the Open Source Definition, not all source available software is FOSS.[54] For example, if the software doesn't meet other aspects of the Open Source Definition such as permitted modification or redistribution, even if the source code is available, the software is not FOSS.[54]

Open-sourcing edit

A recent trend within software companies is open sourcing, or transitioning their previous proprietary software into open source software through releasing it under a open source license.[55][56] Examples of companies who have done this are Google, Microsoft and Apple.[55] Additionally, open sourcing can refer to programming open source software or installing open source software.[56] Open sourcing can be beneficial in multiple ways, such as attracting more external contributors who bring new perspectives and problem solving capabilities. [55] The downsides of open sourcing include the work that has to be done to maintaining the new community, such as making the base code easily understandable, setting up communication channels for new developers and creating documentation to allow new developers to easily join.[55] However, a review of several open sourced projects found that although a newly open sourced project attracts many newcomers, a great amount are likely to soon leave the project and their forks are also likely to not be impactful.[55]

Other edit

Other concepts that may share some similarities to open source are shareware, public domain software, freeware, and software viewers/readers that are freely available but do not provide source code.[43] However, these differ from open source software in access to source code, licensing, copyright and fees.[43]

Current applications and adoption edit

"We migrated key functions from Windows to Linux because we needed an operating system that was stable and reliable – one that would give us in-house control. So if we needed to patch, adjust, or adapt, we could."

Official statement of the United Space Alliance, which manages the computer systems for the International Space Station (ISS), regarding why they chose to switch from Windows to Debian GNU/Linux on the ISS[57][58]

Widely used open-source software edit

Open-source software projects are built and maintained by a network of programmers, who may often be volunteers, and are widely used in free as well as commercial products.[20] Prime examples of open-source products are the Apache HTTP Server, the e-commerce platform osCommerce, internet browsers Mozilla Firefox and Chromium (the project where the vast majority of development of the freeware Google Chrome is done) and the full office suite LibreOffice. One of the most successful open-source products is the Linux operating system, an open-source Unix-like operating system, and its derivative Android, an operating system for mobile devices.[59][60] In some industries, open-source software is common.[61]

Several widely used Python libraries are free and open-source software. These include TensorFlow, PyTorch, scikit-learn, NLTK, OpenCV.

Practical uses edit

Because open-source software generally allows for technology to be more affordable, digital solutions become accessible even in unanticipated fields such as precision agriculture.[62]

Extensions for non-software use edit

While the term "open source" applied originally only to the source code of software,[63] it is now being applied to many other areas[64] such as Open source ecology,[65] a movement to decentralize technologies so that any human can use them. However, it is often misapplied to other areas that have different and competing principles, which overlap only partially.

The same principles that underlie open-source software can be found in many other ventures, such as open-source hardware, Wikipedia, and open-access publishing. Collectively, these principles are known as open source, open content, and open collaboration:[66] "any system of innovation or production that relies on goal-oriented yet loosely coordinated participants, who interact to create a product (or service) of economic value, which they make available to contributors and non-contributors alike."[3]

This "culture" or ideology takes the view that the principles apply more generally to facilitate concurrent input of different agendas, approaches, and priorities, in contrast with more centralized models of development such as those typically used in commercial companies.[67]

See also edit

- Comparison of free and open-source software licenses

- Free software

- Free-software license

- Free software movement

- List of free and open-source software packages

- Free content

- Open-source hardware

- Open Source Initiative

- Open-source license

- Open-source software advocacy

- Open Source Software Institute

- Open-source software security

- Open-source video game

- All articles with titles containing "Open source"

- Proprietary software

- Shared Source Initiative

- Timeline of free and open-source software

- Software composition analysis

References edit

- ^ St. Laurent, Andrew M. (2008). Understanding Open Source and Free Software Licensing. O'Reilly Media. p. 4. ISBN 9780596553951. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ Corbly, James Edward (25 September 2014). "The Free Software Alternative: Freeware, Open Source Software, and Libraries". Information Technology and Libraries. 33 (3): 65. doi:10.6017/ital.v33i3.5105. ISSN 2163-5226. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ a b Levine, Sheen S.; Prietula, Michael J. (30 December 2013). "Open Collaboration for Innovation: Principles and Performance". Organization Science. 25 (5): 1414–1433. arXiv:1406.7541. doi:10.1287/orsc.2013.0872. ISSN 1047-7039. S2CID 6583883.

- ^ Rothwell, Richard (5 August 2008). "Creating wealth with free software". Free Software Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Standish Newsroom — Open Source" (Press release). Boston: Standish Group. 16 April 2008. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "International Authority & Recognition". Opensource.org. 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Perens, Bruce. Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution Archived 15 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. O'Reilly Media. 1999.

- ^ Dibona, Chris; Ockman, Sam (January 1999). The Open Source Definition by Bruce Perens. O'Reilly. ISBN 978-1-56592-582-3.

- ^ "The Open Source Definition". 7 July 2006. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2008., The Open Source Definition according to the Open Source Initiative

- ^ "How Many Open Source Licenses Do You Need? – Slashdot". News.slashdot.org. 16 February 2009. Archived from the original on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Open Source Initiative (24 July 2006). "The Open Source Definition (Annotated)". opensource.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Feller, Joseph; Fitzgerald, Brian; Hissam, Scott; Lakhani, Karim R. (2005). "Introduction". Perspectives on Free and Open Source Software. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. pp. xvii. ISBN 0-262-06246-1.

- ^ Tiemann, Michael. "History of the OSI". Open Source Initiative. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ Stallman, Richard (16 June 2007). "Why "Open Source" misses the point of Free Software". Philosophy of the GNU Project. Free Software Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

As the advocates of open source draw new users into our community, we free software activists have to work even more to bring the issue of freedom to those new users' attention. We have to say, 'It's free software and it gives you freedom!'—more and louder than ever. Every time you say 'free software' rather than 'open source,' you help our campaign.

- ^ Stallman, Richard (19 June 2007). "Why "Free Software" is better than "Open Source"". Philosophy of the GNU Project. Free Software Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 March 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

Sooner or later these users will be invited to switch back to proprietary software for some practical advantage. Countless companies seek to offer such temptation, and why would users decline? Only if they have learned to value the freedom free software gives them, for its own sake. It is up to us to spread this idea—and in order to do that, we have to talk about freedom. A certain amount of the 'keep quiet' approach to business can be useful for the community, but we must have plenty of freedom talk too.

- ^ Stallman, Richard (16 June 2007). "Why "Open Source" misses the point of Free Software". Philosophy of the GNU Project. Free Software Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

Under the pressure of the movie and record companies, software for individuals to use is increasingly designed specifically to restrict them. This malicious feature is known as DRM or Digital Restrictions Management (see DefectiveByDesign.org), and it is the antithesis in spirit of the freedom that free software aims to provide. [...] Yet some open source supporters have proposed 'open source DRM' software. Their idea is that by publishing the source code of programs designed to restrict your access to encrypted media, and allowing others to change it, they will produce more powerful and reliable software for restricting users like you. Then it will be delivered to you in devices that do not allow you to change it. This software might be 'open source,' and use the open source development model; but it won't be free software since it won't respect the freedom of the users that actually run it. If the open source development model succeeds in making this software more powerful and reliable for restricting you, that will make it even worse.

- ^ Rosen, Lawrence. "Joint Works – Open Source Licensing: Software Freedom and Intellectual Property Law". flylib.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Andrew T. Pham, Verint Systems Inc., and Matthew B. Weinstein and Jamie L. Ryerson. "Easy as ABC: Categorizing Open Source Licenses Archived 8 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine"; www.IPO.org. June 2010.

- ^ Shiels, Maggie (14 August 2008). "Legal milestone for open source". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 September 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ^ a b Popp, Karl Michael (2015). Best Practices for commercial use of open source software. Norderstedt, Germany: Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3738619096.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Raymond, Eric (3 October 2005). "The Cathedral and the Bazaar (originally published in Volume 3, Number 3, March 1998)". First Monday. doi:10.5210/fm.v0i0.1472. ISSN 1396-0466.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Robles, Gregorio (2006). "Empirical Software Engineering Research on Free/Libre/Open Source Software". 2006 22nd IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance. pp. 347–350. doi:10.1109/icsm.2006.25. ISBN 0-7695-2354-4. S2CID 6589566. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Napoleao, Bianca M.; Petrillo, Fabio; Halle, Sylvain (2020). "Open Source Software Development Process: A Systematic Review". 2020 IEEE 24th International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference (EDOC). IEEE. pp. 135–144. arXiv:2008.05015. doi:10.1109/EDOC49727.2020.00025. ISBN 978-1-7281-6473-1.

- ^ US Department of Defense. "Open Source Software FAQ". Chief Information Officer. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Sharma, Srinarayan; Vijayan Sugumaran; Balaji Rajagopalan (2002). "A framework for creating hybrid-open source software communities" (PDF). Information Systems Journal. 12: 7–25. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2575.2002.00116.x. S2CID 5815589. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ Landry, John; Rajiv Gupta (September 2000). "Profiting from Open Source". Harvard Business Review. doi:10.1225/F00503 (inactive 31 January 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - ^ Reynolds, Carl; Jeremy Wyatt (February 2011). "Open Source, Open Standards, and Health Care Information Systems". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 13 (1): e24. doi:10.2196/jmir.1521. PMC 3221346. PMID 21447469.

- ^ Nagle, Frank (3 March 2019). "Government Technology Policy, Social Value, and National Competitiveness" (PDF). Information Systems Journal. 12. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3355486. S2CID 85509685. SSRN 3355486.

- ^ Plotkin, Hal (December 1998). "What (and Why) you should know about open-source software". Harvard Management Update: 8–9.

- ^ Payne, Christian (February 2002). "On the Security of Open Source Software". Information Systems Journal. 12 (1): 61–78. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2575.2002.00118.x. S2CID 8123076.

- ^ a b c Boldyreff, Cornelia; Lavery, Janet; Nutter, David; Rank, Stephen. "Open Source Development Processes and Tools" (PDF). Flosshub. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Stansberry, Glen (18 September 2008). "7 Version Control Systems Reviewed – Smashing Magazine". Smashing Magazine. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ a b Frantzell, Lennart (18 July 2016). "GitHub, Launchpad and BitBucket, how today's distributed version control systems are fueling the unprecendented global open source revolution". IBM developerworks. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Baker, Jason. "Top 4 open source issue tracking tools". opensource.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ François Letellier (2008), Open Source Software: the Role of Nonprofits in Federating Business and Innovation Ecosystems, AFME 2008.

- ^ Open Source Software Institute. "Home". Open Source Software Institute. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Hellekson, Gunnar. "Home". Open Source for America. Archived from the original on 1 December 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ from EntandoSrl (Entando ). "Mil-OSS". Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Feller, Joseph; Fitzgerald, Brian; Hissam, Scott; Lakhani, Karim R. (2005). "Introduction". Perspectives on Free and Open Source Software. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. pp. xix.

- ^ Lakhani, Karim R.; Wolf, Robert G. (2005). "Why Hackers Do What They Do: Understanding Motivation and Effort in Free/Open Source Software Projects". In Feller, Joseph (ed.). Perspectives on Free and Open Source Software. The MIT Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-262-06246-1.

- ^ Ghosh, Rishab Aiyer (2005). "Understanding Free Software Developers: Findings from the FLOSS Study". In Feller, Joseph (ed.). Perspectives on Free and Open Source Software. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-262-06246-1.

- ^ a b c d Maracke, Catharina (2019). "Free and Open Source Software and FRAND-based patent licenses: How to mediate between Standard Essential Patent and Free and Open Source Software". The Journal of World Intellectual Property. 22 (3–4): 78–102. doi:10.1111/jwip.12114. ISSN 1422-2213.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Bretthauer, David (2001). "Open Source Software: A History". Information Technology and Libraries. 21 (1).

- ^ a b "International Authority & Recognition". Open Source Initiative. 21 April 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Fogel, Karl (2006). Producing open source software: how to run a successful free software project (1. Aufl., [Nachdr.] ed.). Beijing Köln: O'Reilly. ISBN 978-0-596-00759-1.

- ^ Kelty, Christopher (2008). Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-8900-2.

- ^ a b c Miller, Keith W.; Voas, Jeffrey; Costello, Tom (2010). "Free and Open Source Software". IT Professional. 12 (6): 14–16. doi:10.1109/mitp.2010.147. ISSN 1520-9202. S2CID 265508713.

- ^ a b c d e f g >Tozzi, Christopher (2017). For Fun and Profit: A History of the Free and Open Source Software Revolution. United States: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262341189.

- ^ a b c d Zhu, Kevin Xiaoguo; Zhou, Zach Zhizhong (2012). "Research Note —Lock-In Strategy in Software Competition: Open-Source Software vs. Proprietary Software". Information Systems Research. 23 (2): 536–545. doi:10.1287/isre.1110.0358. ISSN 1047-7047.

- ^ a b "The Open Source Definition (Annotated)". Open Source Initiative. 24 July 2006. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Stallman, Richard (2007). "Why Open Source Misses the Point of Free Software".

- ^ a b c Stallman, Richard M.; Gay, Joshua (2002). Free software, free society. Boston (Mass.): Free software foundation. ISBN 978-1-882114-98-6.

- ^ Brasseur, V. M. (2018). Forge your future with open source: build your skills, build your network, build the future of technology. The pragmatic programmers. Raleigh, North Carolina: The Pragmatic Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-68050-301-2.

- ^ a b c d e Fortunato, Laura; Galassi, Mark (17 May 2021). "The case for free and open source software in research and scholarship". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 379 (2197). Bibcode:2021RSPTA.37900079F. doi:10.1098/rsta.2020.0079. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 33775148. S2CID 232387092.

- ^ a b c d e Pinto, Gustavo; Steinmacher, Igor; Dias, Luiz Felipe; Gerosa, Marco (2018). "On the challenges of open-sourcing proprietary software projects". Empirical Software Engineering. 23 (6): 3221–3247. doi:10.1007/s10664-018-9609-6. ISSN 1382-3256. S2CID 254467440.

- ^ a b Ågerfalk; Fitzgerald (2008). "Outsourcing to an Unknown Workforce: Exploring Opensurcing as a Global Sourcing Strategy". MIS Quarterly. 32 (2): 385. doi:10.2307/25148845. ISSN 0276-7783. JSTOR 25148845.

- ^ Gunter, Joel (10 May 2013). "International Space Station to boldly go with Linux over Windows". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ Bridgewater, Adrian (13 May 2013). "International Space Station adopts Debian Linux, drops Windows & Red Hat into airlock". Computer Weekly. Archived from the original on 24 June 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Michael J. Gallivan, "Striking a Balance Between Trust and Control in a Virtual Organization: A Content Analysis of Open Source Software Case Studies", Info Systems Journal 11 (2001): 277–304

- ^ Hal Plotkin, "What (and Why) you should know about open source software" Harvard Management Update 12 (1998): 8–9

- ^ Noyes, Katherine (18 May 2011). "Open Source Software Is Now a Norm in Businesses". PCWorld. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ dos Santos, Rogério P.; Fachada, Nuno; Beko, Marko; Leithardt, Valderi R. Q. (April 2023). "A Rapid Review on the Use of Free and Open Source Technologies and Software Applied to Precision Agriculture Practices". Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks. 12 (2): 28. doi:10.3390/jsan12020028. hdl:10437/13743. ISSN 2224-2708.

- ^ Stallman, Richard (24 September 2007). "Why "Open Source" misses the point of Free Software". Philosophy of the GNU Project. Free Software Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

However, not all of the users and developers of free software agreed with the goals of the free software movement. In 1998, a part of the free software community splintered off and began campaigning in the name of 'open source.' The term was originally proposed to avoid a possible misunderstanding of the term 'free software,' but it soon became associated with philosophical views quite different from those of the free software movement.

- ^ "What is open source?". Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Open Source Ecology". Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

...building the world's first replicable open source self-sufficient decentralized high-appropriate-tech permaculture ecovillage...

- ^ "Open Collaboration Bitcoin". Informs.org. 2 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ Raymond, Eric S. The Cathedral and the Bazaar. ed 3.0. 2000.

Further reading edit

- Androutsellis-Theotokis, Stephanos; Spinellis, Diomidis; Kechagia, Maria; Gousios, Georgios (2010). "Open source software: A survey from 10,000 feet" (PDF). Foundations and Trends in Technology, Information and Operations Management. 4 (3–4): 187–347. doi:10.1561/0200000026. ISBN 978-1-60198-484-5.

- Coleman, E. Gabriella. Coding Freedom: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Hacking (Princeton UP, 2012)

- Fadi P. Deek; James A. M. McHugh (2008). Open Source: Technology and Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-36775-5.

- Chris DiBona and Sam Ockman and Mark Stone, ed. (1999). Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution. O'Reilly. ISBN 978-1-56592-582-3.

- Joshua Gay, ed. (2002). Free Software, Free Society: Selected Essays of Richard M. Stallman. Boston: GNU Press, Free Software Foundation. ISBN 978-1-882114-98-6.

- Understanding FOSS | editor = Sampathkumar Coimbatore India

- Benkler, Yochai (2002), "Coase's Penguin, or, Linux and The Nature of the Firm." Yale Law Journal 112.3 (Dec 2002): p367(78) (in Adobe pdf format)

- v. Engelhardt, Sebastian (2008). ""The Economic Properties of Software", Jena Economic Research Papers, Volume 2 (2008), Number 2008-045" (PDF). Jena Economics Research Papers.

- Lerner, J. & Tirole, J. (2002): 'Some simple economics on open source', Journal of Industrial Economics 50(2), p 197–234

- Välimäki, Mikko (2005). The Rise of Open Source Licensing: A Challenge to the Use of Intellectual Property in the Software Industry (PDF). Turre Publishing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2009.

- Polley, Barry (11 December 2007). "Open Source Discussion Paper – version 1.0" (PDF). New Zealand Open Source Society. New Zealand Ministry of Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- Rossi, M. A. (2006): Decoding the free/open-source software puzzle: A survey of theoretical and empirical contributions, in J. Bitzer P. Schröder, eds, 'The Economics of Open Source Software Development', p 15–55.

- Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution — an online book containing essays from prominent members of the open-source community

- Berry, D M (2004). The Contestation of Code: A Preliminary Investigation into the Discourse of the Free Software and Open Software Movement, Critical Discourse Studies, Volume 1(1).

- Schrape, Jan-Felix (2017). "Open Source Projects as Incubators of Innovation. From Niche Phenomenon to Integral Part of the Software Industry" (PDF). Stuttgart: Research Contributions to Organizational Sociology and Innovation Studies 2017-03.

- Sustainable Open Source, a Confluence article providing guidelines for fair participation in the open source ecosystem, by Radovan Semancik

External links edit

- The Open Source Initiative's definition of open source

- Free / Open Source Research Community — Many online research papers about Open Source

- Open-source software at Curlie