Lord Peter Wimsey

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2020) |

| Lord Peter Wimsey | |

|---|---|

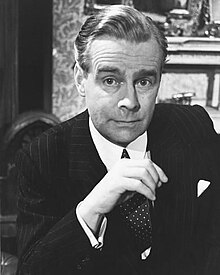

Ian Carmichael as Wimsey in 1972 | |

| First appearance | Whose Body? (1923) |

| Last appearance | The Late Scholar (2013) |

| Created by | Dorothy L. Sayers |

| Portrayed by | Peter Haddon (film) Robert Montgomery (film) Harold Warrender (BBC TV play) Peter Gray (BBC TV play) Ian Carmichael (Television, BBC Radio) Edward Petherbridge (Television, stage play) |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Peter Death Bredon Wimsey |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Aristocrat, amateur Detective, army officer |

| Family | Mortimer Wimsey, 15th Duke of Denver (father) Honoria Delagardie (mother) Gerald Wimsey, 16th Duke of Denver (brother) Lady Mary Wimsey (sister) |

| Spouse | Harriet Vane |

| Children | Bredon Wimsey (son) Roger Wimsey (son) Paul Wimsey (son) |

| Relatives | Paul Delagardie (uncle) Viscount St. George (nephew) Lady Winifred Wimsey (niece) Charles Peter Parker (nephew) Mary Lucasta Parker (niece) Charles Parker (brother-in-law) Helen Wimsey (sister-in-law) |

| Nationality | British |

Lord Peter Death[1] Bredon Wimsey DSO (later 17th Duke of Denver) is the fictional protagonist in a series of detective novels and short stories by Dorothy L. Sayers (and their continuation by Jill Paton Walsh). A dilettante who solves mysteries for his own amusement, Wimsey is an archetype for the British gentleman detective. He is often assisted by his valet and former batman, Mervyn Bunter; by his good friend and later brother-in-law, police detective Charles Parker; and, in a few books, by Harriet Vane, who becomes his wife.

Biography[edit]

Background[edit]

Born in 1890 and ageing in real time, Wimsey is described as being of average height, with straw-coloured hair, a beaked nose, and a vaguely foolish face. Reputedly his looks are patterned after those of academic and poet Roy Ridley,[2] whom Sayers briefly met after witnessing him read his Newdigate Prize-winning poem "Oxford" at the Encaenia ceremony in July 1913. Twice in the novels (in Murder Must Advertise and Busman's Honeymoon) his looks are compared to those of the actor Ralph Lynn. Wimsey also possesses considerable intelligence and athletic ability, evidenced by his playing cricket for Oxford University while earning a First. He creates a spectacularly successful publicity campaign for Whifflet cigarettes while working for Pym's Publicity Ltd, and at age 40 is able to turn three cartwheels in the office corridor, stopping just short of the boss's open office door (Murder Must Advertise).

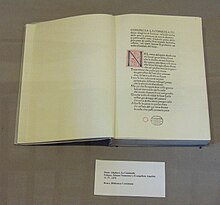

Among Lord Peter's hobbies, in addition to criminology, is collecting incunabula, books from the earliest days of printing. He is an expert on matters of food (and especially wine), male fashion, and classical music. He excels at the piano, including Bach's works for keyboard instruments. Lord Peter likes driving fast and keeps a powerful Daimler (for example, a 12-cylinder or "double-six" 1927 Daimler four-seater); he calls these cars "Mrs Merdle" after a character in Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit who "hated fuss". In the eleventh novel, Busman's Honeymoon, we are told he has owned nine Daimlers with this name.

Lord Peter Wimsey's ancestry begins with the 12th-century knight Gerald de Wimsey, who went with King Richard the Lionheart on the Third Crusade and took part in the Siege of Acre.[3] This makes the Wimseys an unusually ancient family, since "Very few English noble families go that far in the first creation; rebellions and monarchic head choppings had seen to that", as reviewer Janet Hitchman noted in the introduction to Striding Folly. The family coat of arms, first mentioned in Gaudy Night, is "Sable, 3 mice courant, argent; crest, a domestic cat couched as to spring, proper". The family motto, displayed under its coat of arms, is "As my Whimsy takes me."[4]

Early life[edit]

Lord Peter is the second of the three children of Mortimer Wimsey, 15th Duke of Denver, and Honoria Lucasta Delagardie, who lives on throughout the novels as the Dowager Duchess of Denver. She is witty and intelligent, and strongly supports her younger son, whom she plainly prefers over her less intelligent, more conventional older son Gerald, the 16th Duke. Gerald's snobbish wife, Helen, detests Peter. Gerald's son and heir is the devil-may-care Viscount St George. Lady Mary, the younger sister of the 16th Duke, and of Lord Peter, leans strongly to the political left. At one time she planned to elope with a radical left agitator, and though this did not come about she did scandalise Helen by marrying a policeman of working-class origins.

Lord Peter Wimsey is called "Lord" as he is the younger son of a duke. This is a courtesy title; he is not a peer and has no right to sit in the House of Lords, nor does the courtesy title pass on to any offspring he may have.

As a boy, Peter was, to the great distress of his father, strongly attached to an old, smelly poacher living at the edge of the family estate. In his youth, Peter was influenced by his maternal uncle, Paul Delagardie, who took it upon himself to instruct his nephew in the facts of life – how to conduct various love affairs and treat his lovers. Lord Peter was educated at Eton College and Balliol College, Oxford, graduating with a first-class degree in history. He was also an outstanding cricketer, whose performance was still well remembered decades later. Though not taking up an academic career, he was left with an enduring and deep love for Oxford.

Great War and aftermath[edit]

To his uncle's disappointment, Wimsey fell deeply in love with a young woman named Barbara and became engaged to her. When the First World War broke out, he hastened to join the British Army, releasing Barbara from her engagement in case he was killed or mutilated. The girl later married another, less principled officer.

Wimsey served on the Western Front from 1914 to 1918, reaching the rank of Major in the Rifle Brigade. He was appointed an intelligence officer, and on one occasion he infiltrated the staff room of a German officer.[5] Though not explicitly stated, that feat implies that Wimsey spoke a fluent and unaccented German. As noted in Have His Carcase, he communicated at that time with British Intelligence using the Playfair cipher and became proficient in its use.

For reasons never clarified, after the end of his spy mission, Wimsey in the later part of the war moved from Intelligence and resumed the role of a regular line officer. He was a conscientious and effective commanding officer, popular with the men under his command—an affection still retained by Wimsey's former soldiers many years after the war, as is evident from a short passage in Clouds of Witness and an extensive reminiscence in Gaudy Night.

In particular, while in the army he met Sergeant Mervyn Bunter, who had previously been in service. In 1918, Wimsey was wounded by artillery fire near Caudry in France. He suffered a breakdown due to shell shock (which we now call post-traumatic stress disorder but which was then often thought, by those without first-hand experience of it, to be a species of malingering) and was eventually sent home. While sharing this experience, which the Dowager Duchess referred to as "a jam", Wimsey and Bunter arranged that if they were both to survive the war, Bunter would become Wimsey's valet. Throughout the books, Bunter takes care to address Wimsey as "My Lord". Nevertheless, he is a friend as well as a servant, and Wimsey again and again expresses amazement at Bunter's high efficiency and competence in virtually every sphere of life.

After the war, Wimsey was ill for many months, recovering at the family's ancestral home in Duke's Denver, a fictional setting—as is the Dukedom of Denver—about 15 miles (24 km) beyond the real Denver in Norfolk, on the A10 near Downham Market. Wimsey was for a time unable to give servants any orders whatsoever, since his wartime experience made him associate the giving of an order with causing the death of the person to whom the order was given. Bunter arrived and, with the approval of the Dowager Duchess, took up his post as valet. Bunter moved Wimsey to a London flat at 110A Piccadilly, W1,[6] while Wimsey recovered. Even much later, however, Wimsey would have relapses—especially when his actions caused a murderer to be hanged. As noted in Whose Body?, on such occasions Bunter would take care of Wimsey and tenderly put him to bed, and they would revert to being "Major Wimsey" and "Sergeant Bunter".

In the reissue of The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (1935), the biography of Wimsey is "brought up to date" by his uncle, Paul Austin Delagardie, purportedly at the request of Sayers herself, further giving the illusion that he is a real person. At this point, Wimsey is claimed to be 45 years old and "time he was settled". The biography takes up the last eight pages of the book and concludes with the statement that Wimsey "has always had everything except the things he really wanted, and I suppose he is luckier than most."

Detective work[edit]

Wimsey begins his hobby of investigation by recovering The Attenbury Emeralds in 1921. At the beginning of Whose Body?, there appears the unpleasant Inspector Sugg, who is extremely hostile to Wimsey and tries to exclude him from the investigation (reminiscent of the relations between Sherlock Holmes and Inspector Lestrade). However, Wimsey is able to bypass Sugg through his friendship with Scotland Yard detective Charles Parker, a sergeant in 1921. At the end of Whose Body?, Wimsey generously allows Sugg to take completely undeserved credit for the solution; the grateful Sugg cannot go on with his hostility to Wimsey. In later books, Sugg fades away and Wimsey's relations with the police become dominated by his amicable partnership with Parker, who eventually rises to the rank of Commander (and becomes Wimsey's brother-in-law).

Bunter, a man of many talents himself, not least photography, often proves instrumental in Wimsey's investigations. However, Wimsey is not entirely well. At the end of the investigation in Whose Body? (1923), Wimsey hallucinates that he is back in the trenches. He soon recovers his senses and goes on a long holiday.

In Clouds of Witness (1926), Wimsey travels to the fictional Riddlesdale in North Yorkshire to assist his elder brother Gerald, who has been accused of murdering Captain Denis Cathcart, their sister's fiancé. As Gerald is the Duke of Denver, he is tried by the entire House of Lords, as required by the law at that time, to much scandal and the distress of his wife Helen. Their sister, Lady Mary, also falls under suspicion. Lord Peter clears the Duke and Lady Mary, to whom Parker is attracted.

As a result of the slaughter of men in the First World War, there was in the UK a considerable imbalance between the sexes. It is not exactly known when Wimsey recruited Miss Climpson to run an undercover employment agency for women, a means to garner information from the otherwise inaccessible world of spinsters and widows, but it is prior to Unnatural Death (1927), in which Miss Climpson assists Wimsey's investigation of the suspicious death of an elderly cancer patient. Wimsey's highly effective idea is that a male detective going around and asking questions is likely to arouse suspicion, while a middle-aged woman doing it would be dismissed as a gossip and people would speak openly to her.

As recounted in the short story "The Adventurous Exploit of the Cave of Ali Baba", in December 1927 Wimsey fakes his own death, supposedly while hunting big game in Tanganyika, to penetrate and break up a particularly dangerous and well-organised criminal gang. Only Wimsey's mother and sister, the loyal Bunter and Inspector Parker know he is still alive. Emerging victorious after more than a year masquerading as "the disgruntled sacked servant Rogers", Wimsey remarks that "We shall have an awful time with the lawyers, proving that I am me." In fact, he returns smoothly to his old life, and the interlude is never referred to in later books.

During the 1920s, Wimsey has affairs with various women, which are the subject of much gossip in Britain and Europe. This part of his life remains hazy: it is hardly ever mentioned in the books set in the same period; most of the scant information on the subject is given in flashbacks from later times, after he meets Harriet Vane and relations with other women become a closed chapter. In Busman's Honeymoon Wimsey facetiously refers to a gentleman's duty "to remember whom he had taken to bed" so as not to embarrass his bedmate by calling her by the wrong name.

There are several references to a relationship with a famous Viennese opera singer, and Bunter—who evidently was involved with this, as with other parts of his master's life—recalls Wimsey being very angry with a French mistress who mistreated her own servant.

The only one of Wimsey's earlier women to appear in person is the artist Marjorie Phelps, who plays an important role in The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club. She has known Wimsey for years and is attracted to him, though it is not explicitly stated whether they were lovers. Wimsey likes her, respects her, and enjoys her company—but that is not enough. In Strong Poison, she is the first person other than Wimsey himself to realise that he has fallen in love with Harriet.

Reviewer Barbara Stanton noted that "Dorothy Sayers had created Peter Wimsey as a womanizer - though a rather gentlemanly and sensitive one. It would have been out of character for him to return Marjorie Phelps' love, and inevitable that he would break her heart - as he must have done to many other women before. But Sayers - a woman writer who had herself experienced disappointments and frustrations in relations with men - evidently decided to take revenge on her character and educate him. Sayers took the conscious decision to turn the tables on Wimsey and make him fall deeply in love with a woman who would make him sweat and wait very very long before she finally accepted him".[7]

In Strong Poison Lord Peter encounters Harriet Vane, a cerebral, Oxford-educated mystery writer, while she is on trial for the murder of her former lover in December 1929. He falls in love with her at first sight. He saves Harriet from the gallows, but she believes that gratitude is not a good foundation for marriage, and politely but firmly declines his frequent proposals. Lord Peter encourages his friend and foil, Chief Inspector Charles Parker, to propose to his sister, Lady Mary Wimsey, despite the great difference in their rank and wealth. They marry and have a son, named Charles Peter ("Peterkin"), and a daughter, Mary Lucasta ("Polly"). Visiting the Fen country in Easter 1930[citation needed] (in The Nine Tailors) Wimsey must unravel a 20-year-old case of missing jewels, an unknown corpse, a missing World War I soldier believed alive, a murderous escaped convict believed dead, and a mysterious code concerning church bells.[8]

While on a fishing holiday in Scotland later in 1930,[citation needed] Wimsey takes part in the investigation of the murder of an artist, related in Five Red Herrings. Despite her rejection of his marriage proposals, he continues to court Miss Vane. In Have His Carcase, in 1931, he finds Harriet is not in London, but learns from a reporter that she has discovered a corpse while on a walking holiday on England's south coast. Wimsey is at her hotel the next morning. He not only investigates the death and offers proposals of marriage, but also acts as Harriet's patron and protector from press and police. Despite a prickly relationship, they work together to identify the murderer.

Back in London in 1932, Wimsey goes undercover as "Death Bredon" at an advertising firm, working as a copywriter (Murder Must Advertise). Bredon is framed for murder, leading Charles Parker to "arrest" Bredon for murder in front of numerous witnesses. To distinguish Death Bredon from Lord Peter Wimsey, Parker smuggles Wimsey out of the police station and urges him to get into the papers. Accordingly, Wimsey accompanies "a Royal personage" to a public event, leading the press to carry pictures of both "Bredon" and Wimsey.

By 1935 Lord Peter is in continental Europe, acting as an unofficial attaché to the British Foreign Office (at the time of writing, British diplomacy was much concerned with the impending Italian invasion of Ethiopia). Harriet Vane contacts him about a problem she has been asked to investigate in her college at Oxford (Gaudy Night). At the end of their investigation, Vane finally accepts Wimsey's proposal of marriage.

The couple marry on 8 October 1935, at St Cross Church, Oxford, as depicted in the opening collection of letters and diary entries in Busman's Honeymoon. The Wimseys honeymoon at Talboys, a house in east Hertfordshire near Harriet's childhood home, which Peter has bought for her as a wedding present. There they find the body of the previous owner, and spend their honeymoon solving the case, thus having the aphoristic "Busman's Honeymoon".

Over the next five years, according to Sayers' short stories, the Wimseys have three sons: Bredon Delagardie Peter Wimsey (born in October 1936 in the story "The Haunted Policeman"); Roger Wimsey (born 1938), and Paul Wimsey (born 1940). However, according to the wartime publications of The Wimsey Papers, published in The Spectator, the second son was called Paul. In The Attenbury Emeralds, Paul is again the second son and Roger is the third son. In the subsequent The Late Scholar, Roger is not mentioned at all. It may be presumed that Paul is named after Lord Peter's maternal uncle Paul Delagardie. "Roger" is an ancestral Wimsey name.

In Sayers's final Wimsey story, the 1942 short story "Talboys", Peter and Harriet are enjoying rural domestic bliss with their three sons when Bredon, their first-born, is accused of the theft of prize peaches from the neighbour's tree. Peter and the accused set off to investigate and, of course, prove Bredon's innocence.

Fictional bibliography[edit]

Wimsey is described as having authored numerous books, among them the following fictitious works:

- Notes on the Collecting of Incunabula

- The Murderer's Vade-Mecum

The stories[edit]

Dorothy Sayers wrote 11 Wimsey novels and a number of short stories featuring Wimsey and his family. Other recurring characters include Inspector Charles Parker, the family solicitor Mr Murbles, barrister Sir Impey Biggs, journalist Salcombe Hardy, and family friend and financial whiz the Honourable Freddy Arbuthnot, who finds himself entangled in the case in the first of the Wimsey books, Whose Body? (1923).

Sayers wrote no more Wimsey murder mysteries, and only one story involving him, after the outbreak of World War II. In The Wimsey Papers, a series of fictionalised commentaries in the form of mock letters between members of the Wimsey family published in The Spectator, there is a reference to Harriet's difficulty in continuing to write murder mysteries at a time when European dictators were openly committing mass murders with impunity; this seems to have reflected Sayers' own wartime feeling.

The Wimsey Papers included a reference to Wimsey and Bunter setting out during the war on a secret mission of espionage in Europe, and provide the ironic epitaph Wimsey writes for himself: "Here lies an anachronism in the vague expectation of eternity". The papers also incidentally show that in addition to his thorough knowledge of the classics of English literature, Wimsey is familiar — though in fundamental disagreement — with the works of Karl Marx, and well able to debate with Marxists on their home ground.

The only occasion when Sayers returned to Wimsey was the 1942 short story "Talboys". The story is set in a quiet rural environment, the war at that time devastating Europe received only a single oblique reference, and the case Wimsey undertakes is just to clear his young son of the false accusation of stealing fruit from the neighbour's tree. Though Sayers lived until 1957, she never again took up the Wimsey books after this final effort.

Jill Paton Walsh wrote about Wimsey's career through and beyond the Second World War. In the continuations Thrones, Dominations (1998), A Presumption of Death (2002), The Attenbury Emeralds (2010), and The Late Scholar (2014), Harriet lives with the children at Talboys, Wimsey and Bunter have returned successfully from their secret mission in 1940, and his nephew Lord St. George is killed while serving as an RAF pilot in the Battle of Britain. Consequently, when Wimsey's brother dies of a heart attack in 1951 during a fire in Bredon Hall, Wimsey becomes — very reluctantly — the Duke of Denver. Their Graces are then drawn into a mystery at a fictional Oxford college.

Origins[edit]

In How I Came to Invent the Character of Lord Peter Wimsey,[9] Sayers wrote:

Lord Peter's large income... I deliberately gave him... After all it cost me nothing and at the time I was particularly hard up and it gave me pleasure to spend his fortune for him. When I was dissatisfied with my single unfurnished room I took a luxurious flat for him in Piccadilly. When my cheap rug got a hole in it, I ordered him an Aubusson carpet. When I had no money to pay my bus fare I presented him with a Daimler double-six, upholstered in a style of sober magnificence, and when I felt dull I let him drive it. I can heartily recommend this inexpensive way of furnishing to all who are discontented with their incomes. It relieves the mind and does no harm to anybody.

Janet Hitchman, in the preface to Striding Folly, remarks that "Wimsey may have been the sad ghost of a wartime lover(...). Oxford, as everywhere in the country, was filled with bereaved women, but it may have been more noticeable in university towns where a whole year's intake could be wiped out in France in less than an hour." There is, however, no verifiable evidence of any such World War I lover of Sayers on whom the character of Wimsey might be based.

Another theory is that Wimsey was based, at least in part, on Eric Whelpton, who was a close friend of Sayers at Oxford. Ian Carmichael, who played the part of Wimsey in the first BBC television adaptation and studied the character and the books thoroughly, said that the character was Sayers' conception of the 'ideal man', based in part on her earlier romantic misfortunes.

Another theory is that Wimsey was based, at least in part, on Philip Trent, created by E. C. Bentley in the novel Trent's Last Case. Dorothy Sayers greatly admired that book.

Social satire[edit]

Many episodes in the Wimsey books express a mild satire on the British class system, in particular in depicting the relationship between Wimsey and Bunter. The two of them are clearly the best and closest of friends, yet Bunter is invariably punctilious in using "my lord" even when they are alone, and "his lordship" in company. In a brief passage written from Bunter's point of view in Busman's Honeymoon Bunter is seen, even in the privacy of his own mind, to be thinking of his employer as "His Lordship". Wimsey and Bunter even mock the Jeeves and Wooster relationship.

In Whose Body?, when Wimsey is caught by a severe recurrence of his First World War shell-shock and nightmares and being taken care of by Bunter, the two of them revert to being "Major Wimsey" and "Sergeant Bunter". In that role, Bunter, sitting at the bedside of the sleeping Wimsey, is seen to mutter affectionately, "Bloody little fool!"[10]

In "The Vindictive Story of the Footsteps That Ran", the staunchly democratic Dr Hartman invites Bunter to sit down to eat together with himself and Wimsey, at the doctor's modest apartment. Wimsey does not object, but Bunter strongly does: "If I may state my own preference, sir, it would be to wait upon you and his lordship in the usual manner". Whereupon Wimsey remarks: "Bunter likes me to know my place".[11]

At the conclusion of Strong Poison, Inspector Parker asks "What would one naturally do if one found one's water-bottle empty?" (a point of crucial importance in solving the book's mystery). Wimsey promptly answers, "Ring the bell", whereupon Miss Murchison, the indefatigable investigator employed by Wimsey for much of this book, comments "Or, if one wasn't accustomed to be waited on, one might use the water from the bedroom jug."

George Orwell was highly critical of this aspect of the Wimsey books: "... Even she [Sayers] is not so far removed from Peg's Paper as might appear at a casual glance. It is, after all, a very ancient trick to write novels with a lord for a hero. Where Miss Sayers has shown more astuteness than most is in perceiving that you can carry that kind of thing off a great deal better if you pretend to treat it as a joke. By being, on the surface, a little ironical about Lord Peter Wimsey and his noble ancestors, she is enabled to lay on the snobbishness ('his lordship' etc.) much thicker than any overt snob would dare to do".[12]

Dramatic adaptations[edit]

Film[edit]

In 1935, the British film The Silent Passenger was released, in which Lord Peter, played by well-known comic actor Peter Haddon, solved a mystery on the boat train crossing the English Channel. Sayers disliked the film and James Brabazon describes it as an "oddity, in which Dorothy's contribution was altered out of all recognition."

The novel Busman's Honeymoon was originally a stage play by Sayers and her friend Muriel St. Clare Byrne. A 1940 film of Busman's Honeymoon (US: The Haunted Honeymoon), stars Robert Montgomery and Constance Cummings as Lord and Lady Peter and Seymour Hicks as Bunter.

Television[edit]

A BBC television version of the play Busman's Honeymoon with Harold Warrender as Lord Peter, was transmitted live on the BBC Television Service on 2 October 1947.[13] A second live BBC version was broadcast on 3 October 1957, with Peter Gray as Wimsey.[14]

Several other Lord Peter Wimsey novels were made into television productions by the BBC, in two separate series. Wimsey was played by Ian Carmichael, with Bunter being played by Glyn Houston (with Derek Newark stepping in for The Unpleasantness at The Bellona Club), in a series of separate serials under the umbrella title Lord Peter Wimsey, that ran between 1972 and 1975, adapting five novels (Clouds of Witness, The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, Five Red Herrings, Murder Must Advertise and The Nine Tailors).

Edward Petherbridge played Lord Peter for BBC Television in 1987, in which three of the four major Wimsey/Vane novels (Strong Poison, Have His Carcase and Gaudy Night) were dramatised under the umbrella title A Dorothy L. Sayers Mystery. Harriet Vane was played by Harriet Walter and Bunter was played by Richard Morant. The BBC was unable to secure the rights to turn Busman's Honeymoon into a proposed fourth and last part of the planned 13-episode series, so the series was produced as ten episodes. (Edward Petherbridge later played Wimsey in the UK production of the Busman's Honeymoon play staged at the Lyric Hammersmith and on tour in 1988, with the role of Harriet being taken by his real-life spouse, Emily Richard.)

Both sets of adaptations were critically successful, with both Carmichael and Petherbridge's respective performances being widely praised. However, the two portrayals are quite different from one another: Carmichael's Peter is eccentric, jolly and foppish with occasional glimpses of the inner wistful, romantic soul, whereas Petherbridge's portrayal was more calm, solemn and had a stiff upper lip, subtly downplaying many of the character's eccentricities. Both the 1970s productions and the 1987 series are now available on videotape and DVD.

Radio[edit]

Adaptations of the Lord Peter Wimsey novels appeared on BBC Radio from the 1930s onwards. An adaptation of the short story "The Footsteps That Ran" dramatised by John Cheatle appeared on the BBC Home Service in November 1939 with Cecil Trouncer as Wimsey.[15] Rex Harrison took on the role in an adaptation of "Absolutely Everywhere" on the Home Service on 5 March 1940.[16] The short story "The Man with No Face" was dramatised by Audrey Lucas for the Home Service Saturday-Night Theatre play, broadcast on 3 April 1943 with Robert Holmes in the lead role.[17]

A four-part adaptation of The Nine Tailors adapted by Giles Cooper and starring Alan Wheatley as Wimsey was broadcast on the BBC Light Programme in August 1954.[18]

Ian Carmichael reprised his television role as Lord Peter in ten radio adaptations for BBC Radio 4 of Sayers's Wimsey novels between 1973 and 1983, all of which have been available on cassette and CD from the BBC Radio Collection. These co-starred Peter Jones as Bunter. In the original series no adaptation was made of the seminal Gaudy Night, perhaps because the leading character in this novel is Harriet and not Peter; this was corrected in 2005 when a version specially recorded for the BBC Radio Collection was released starring Carmichael and Joanna David. The CD also includes a panel discussion on the novel, the major participants in which are P. D. James and Jill Paton Walsh. Gaudy Night was released as an unabridged audio book read by Ian Carmichael in 1993.

Gary Bond starred as Lord Peter Wimsey and John Cater as Bunter in two single-episode BBC Radio 4 adaptations: The Nine Tailors on 25 December 1986 and Whose Body on 26 December 1987.[19] Simon Russell Beale played Wimsey in an adaptation of Strong Poison dramatised by Michael Bakewell in 1999.[20]

Bibliography[edit]

Novels[edit]

With year of first publication

- Whose Body? (1923)

- Clouds of Witness (1926)

- Unnatural Death (1927) (U.S. title originally The Dawson Pedigree)

- The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (1928)

- Strong Poison (1930)

- The Five Red Herrings (1931)

- Have His Carcase (1932)

- Murder Must Advertise (1933)

- The Nine Tailors (1934)

- Gaudy Night (1935)

- Busman's Honeymoon (1937)

- Thrones, Dominations (1998) Unfinished Sayers manuscript completed by Jill Paton Walsh

Short story collections[edit]

- Lord Peter Views the Body (1928)

- Hangman's Holiday (1933) Also contains non-Wimsey stories

- In the Teeth of the Evidence (1939) Also contains non-Wimsey stories

- Striding Folly (1972)

- Lord Peter (1972)

Uncollected Lord Peter Wimsey stories[edit]

- The Locked Room. Bodies from the Library: Volume 2, Ed. Tony Medawar (HarperCollins, 2019).

In addition there are

- The Wimsey Papers, published between Nov. 1939 and Jan. 1940 in The Spectator Magazine—a series of mock letters by members of the Wimsey family, being in effect fictionalised commentaries on life in England in the early months of the war.

Books about Lord Peter by other authors[edit]

- Ask a Policeman (1934), a collaborative novel by members of The Detection Club, wherein several authors 'exchanged' detectives. The Lord Peter Wimsey sequence was penned by Anthony Berkeley.

- The Wimsey Family: A Fragmentary History compiled from correspondence with Dorothy L. Sayers (1977) by C. W. Scott-Giles, Victor Gollancz, London. ISBN 0-06-013998-6

- Lord Peter Wimsey Cookbook (1981) by Elizabeth Bond Ryan and William J. Eakins ISBN 0-89919-032-4

- The Lord Peter Wimsey Companion (2002) by Stephan P. Clarke ISBN 0-89296-850-8 published by The Dorothy L. Sayers Society.

- Conundrums for the Long Week-End : England, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Lord Peter Wimsey (2000) by Robert Kuhn McGregor, Ethan Lewis ISBN 0-87338-665-5

- A Presumption of Death (2002) by Jill Paton Walsh

- The Attenbury Emeralds (2010) by Jill Paton Walsh

- The Late Scholar (2014) by Jill Paton Walsh

Lord Peter Wimsey has also been included by the science fiction writer Philip José Farmer as a member of the Wold Newton family.

References[edit]

- ^ The name Death is usually pronounced /ˈdiːθ/, but in Murder Must Advertise Lord Peter (investigating under cover under the name Death Bredon) says "It's spelt Death. Pronounce it any way you like. Most of the people who are plagued with it make it rhyme with teeth, but personally I think it sounds more picturesque when rhymed with breath."

- ^ Reynolds, Barbara (1997). Dorothy L. Sayers, Her Life and Soul. New York, New York, USA: St. Martin's Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780312153533.

- ^ Strong Poison, Ch. XXI.

- ^ Clouds of Witness reissue, Dorothy Sayers. London: Victor Gollancz, 1935 (preface)

- ^ Whose Body?, Ch.11

- ^ Although London postal districts were subdivided into numbered divisions in 1917, the books merely refer to the postal district as "W".

- ^ Barbara Stanton, "Harriet Vane and Peter Wimsey re-examined" in Margaret G. Crawford (ed.) "Assertive Women in Early Twentieth Century Popular Literature", 1996 Semi-Annual North American Academic Round Table on Gender Roles, p. 77-78

- ^ "Timeline of Lord Peter's Life".

- ^ Barbara Reynolds, Dorothy L. Sayers: Her Life and Soul, "not entirely accurate, but why should it be?", p. 230.

- ^ Whose Body?, ch. 8

- ^ Quoted in Frederick B. Gowan, "The Decline and Transformation of the British Class System", pp. 45, 73

- ^ Orwell's review of Gaudy Night in the New English Weekly, 23 January 1936, reprinted in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Penguin Books, London, 1970, Vol.1, P.186

- ^ "Busman's Honeymoon (1947)". BBC Genome. 2 October 1947. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Busman's Honeymoon (1957)". BBC Genome. 3 October 1957. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "The Footsteps That Ran". BBC Genome. 26 November 1939. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Absolutely Everywhere". BBC Genome. 5 March 1940. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "The Man With No Face". BBC Genome. 3 April 1943. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "The Nine Tailors". BBC Genome. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Lord Peter Wimsey

- ^ "Strong Poison". BBC Genome. 2 October 1999. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

External links[edit]

- Literary characters introduced in 1923

- Characters in British novels of the 20th century

- Dorothy L. Sayers characters

- Fictional amateur detectives

- Fictional gentleman detectives

- Fictional people educated at Eton College

- Fictional University of Oxford people

- Fictional World War I veterans

- Fictional characters with post-traumatic stress disorder

- Fictional cricketers

- Novel series

- People associated with Balliol College, Oxford